La Fantastica

Emerging artists: Sara Basta and John Cascone

Residency place: Latitudo Art Projects (Rome, Italy)

The issue of the urban periphery and its residents is a cornerstone for change, especially in a large metropolis like Rome. The third year of MagiC Carpets Italy draws its inspiration from people who have long told the stories of the suburbs – like Pier Paolo Pasolini – and from those who used social issues to activate new processes of invention – like Gianni Rodari.

This year, which marked one hundred years since Gianni Rodari’s birth, we wanted to create a portrait of this corner of Rome, between Via Portuense and the curves of the Tiber, encompassing the Trullo and the Corviale. Through the creative process inherent to human nature, to quote Rodari – in this case, the creative process of artists John Cascone and Sara Basta and the Lithuanian photographer Mykolas Juodelė – we rediscovered these areas of Rome. The Trullo was a focus of Rodari himself, who wrote A Pie in the Sky in 1966. In the story, a spaceship, anything but alien, lands on Monte Cucco, and the neighbourhood’s children share it with all the children of Rome. Pier Paolo Pasolini also lingered in these areas of the Roman countryside, where the writer from Casarsa filmed scenes of his famous film, The Hawks and the Sparrows. At the Trullo, they played football: “Fermete, a Pà. dà du carci co’ nnoi!” (“Hey Pasolini, kick the ball around with us!” Partitella al Trullo, 1963). This was the call of the street kids, as they begged the Friulian writer to join their improvised football matches on the dusty fields of the Roman periphery.

With three artists, each very different from the next, we set out to discover these places, with the images and stories of Rodari and Pasolini always in the background.

The stories from Pasolini’s The Street Kids have become a way to appropriate certain places in the periphery. The words of the Friulian writer become a lens for a foreign photographer, to understand these areas and reinterpret the faces of today with the eyes of the past.

And Rodari’s words have now become a system to set off a procreative process for new experiences and new works, as in the case of the two Italian artists, Sara Basta and John Cascone.

A FANTASTICA TO OPEN UP TO THE WORLD

“If we had a Fantastic in the manner we have a Logic, the art of invention would have been invented. To some extent aesthetics belong to the Fantastic, much like judgement does to Logic.”

Novalis, Fragment 1905

Gianni Rodari found this short fragment from the German poet Novalis in the winter of 1937-38, when he was teaching Italian to a family of German Jewish refugees in Italy. It is with this backdrop that the Omegna master’s path begins. It defines the structure he uses to build an art that identifies the mechanisms of creative imagination. And it is exactly from this premise that our journey through the Trullo neighbourhood begins, through the art of Sara Basta and John Cascone.

Gianni Rodari provides the context to start from. His fairy tales, whether passed down to us by our parents or discovered when we were grown, taught us a new way of looking at the world, listening to it through and through. It is from the combination of logic and an almost scientific way of observing reality that we arrive to the Fantastica – which does not signify an escape, but a way to be wholly involved with the instruments we are given.

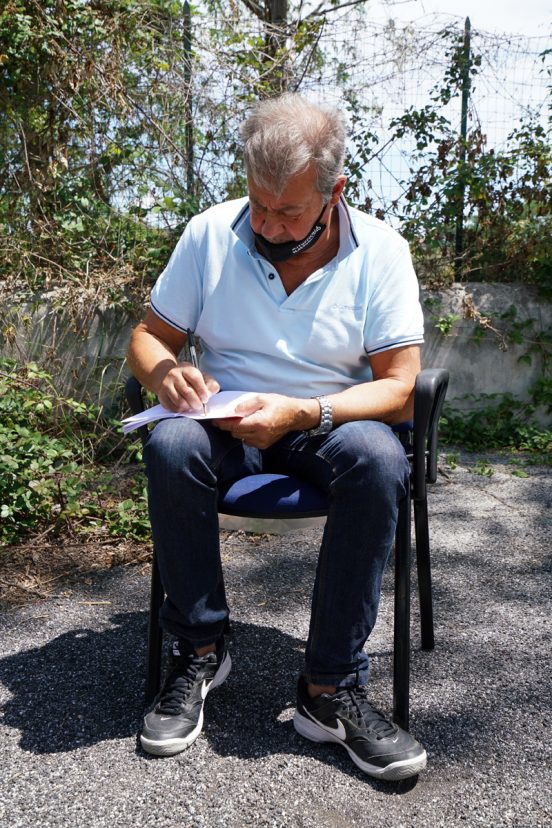

Following Rodari’s methodology, we had to be daring, we had to analyse the neighbourhood face-to-face. There we were in the Trullo quarter, or rather working-class suburb, as Aldo reminded us during one of our first wanderings in the neighbourhood, built by the Fascist regime starting in 1938, southwest of the capital and completely isolated from the rest of the city. Even now that the city has spread out and residential zones like the Corviale and Casetta Mattei have sprung up, the Trullo seems to belong to its own world. Its buildings have a rationalistic inclination – low, with modular housing: every aspect maintains the most rigorous and geometric essentiality. The public housing that runs along Via del Trullo is a world to its own, wedged between the Monte delle Capre and Montecucco.

The three-story buildings are coloured with murals and poetry. This strong narrative expands from images and words to music, painting and cinema. The internal alleyways running between the buildings parallel to Via del Trullo lead to large courtyards with a marked social aim, where laundry is hung, kids play football and people stop to chat. The parish with its oratory, the San Raffaele Theatre, the local market. A town, where everyone knows each other, fairly self-sufficient.

A periphery, both physically and mentally: here, periphery means feeling part of a place unto itself.

After our first foray into the neighbourhood, we carefully went through the recording of Aldo’s words, sometimes fluid and other times tangled, trying to capture its essence. He loves the neighbourhood, or better, has learned to love it and maintain its memories. He says he is the oldest tenant of the eighth lot and wants to pass its important heritage on to others.

Many narratives follow Aldo’s story: Anna experiences the neighbourhood, after many years working in a large institution that took her far from it, almost as a foreigner; Mario in the Trullo is a director of spontaneous, generous, initiatives that stay away from local politics but have a clear political value; and finally Ilaria, a scholar, an enthusiast and expert on Rodari, who wants to somehow pass his legacy on to us.

After many wanderings through the Trullo, Gianni Rodari is again predominant – not only for his famous story A Pie in the Sky, originating right here at Collodi Elementary School with the students of Ms Bigiaretti – but for his art, able to identify the mechanisms of creative imagination, which acts on reality. Rodari manages to weave a story of ordinary science fiction, in a saraband of joyous inventions, in a world where anything is possible, even atomic weapons turning into tasty chocolate cakes.

John Cascone, mindful of Rodari’s lesson and with the approach of a scientist, allowed himself the luxury of looking at this corner of Rome from above, going against the experience of the world as we know it, dominated by the law of gravity. Aware of the rules to access reality from the front door, he chose to go in through a window, through the eyes of those who experience it. This window led him to “artefacts”, banal and common, taken from daily life, that tell the story of a neighbourhood, the Trullo, through the fantasy of those who know it well. Through an unconventional perspective, we see manholes turn into in passageways to the subsoil, pylons that become electric giants, or trees without leaves transformed into beautiful fossil plants. The documentary filmed in the Trullo, as the artist says, came together biologically: in the background, seven stories from Annalisa, Ida, Giancarlo, Anna, Elisa, Siria and Filippo make up the individual cellular organisms of a species. The stories show the gradual evolution of seven single cells that have created an amazing multi-cellular organism. The documentary – as a living organism – came together in the final work Metamorfica, enriched along the way by other forms, like the booklet of the Enciclopedia de La Fantastica, which was distributed by Spores: young people that spread the secret art of creativity as if it were pollen on last day of the Festival. John says: “I thought I would bring these stories back to the place, imagining an advertising campaign, entitled Spore, as a way to multiply these stories.” The final form of this gradual biological growth, a choreography designed with a figure skater from the Polisportiva Trullo, was composed of exactly seven movements, undergoing a final transformation from chrysalis to butterfly.

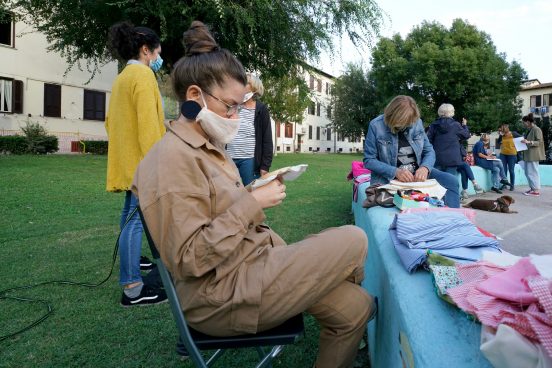

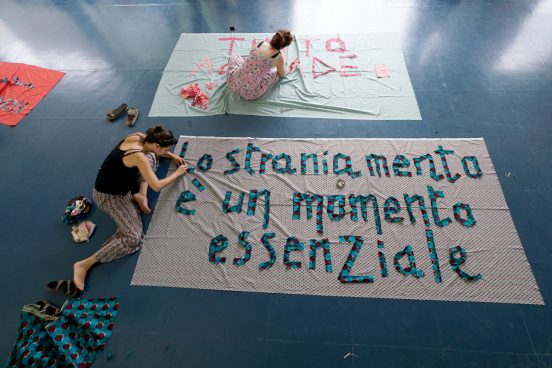

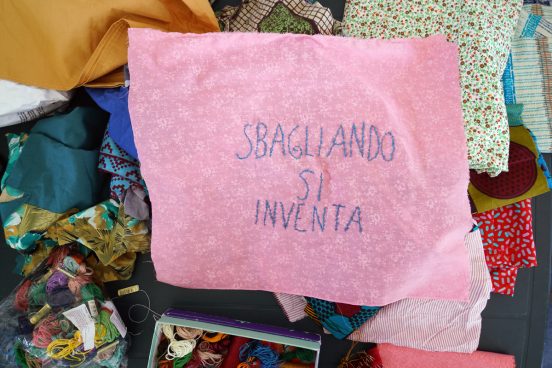

With Sara Basta, the process was different. Her approach seems to conform to the creative aspect of language use, and by tying language to emotional connection, she creates a combinatorial machine to generate new flows and new relationships. The foundations for this Moto perpetuo combinatorio, to use the title of the artist’s work, are Rodari’s words from the Grammar of Fantasy.

The idea of language as a combinatorial machine has inspired many writers, and it appears that Sara wanted to draw on not only Rodari’s words, but on ancient technique as well. All of this takes shape in the video: the phrases and words of Rodari, sewn and embroidered during the workshops, mix together individual stories of lived experiences, entwining with one another. The participants do not give voice to their own stories, but appropriate, transform and interpret the stories of the others.

Fascinated by the potential of language and the infinite number of phrases that make up an alphabet primer, watching Sara’s video, I thought of a passage from Gulliver’s Travels:

He then led me to the frame… twenty feet square, placed in the middle of the room. The superfices was composed of several bits of wood, about the bigness of a die, but some larger than others. They were all linked together by slender wires. These bits of wood were covered, on every square, with paper pasted on them; and on these papers were written all the words of their language, in their several moods, tenses, and declensions; but without any order. The professor then desired me “to observe; for he was going to set his engine at work.” The pupils, at his command, took each of them hold of an iron handle, whereof there were forty fixed round the edges of the frame; and giving them a sudden turn, the whole disposition of the words was entirely changed. […] This work was repeated three or four times, and at every turn, the engine was so contrived, that the words shifted into new places, as the square bits of wood moved upside down. Six hours a day the young students were employed in this labour; and the professor showed me several volumes in large folio, already collected, of broken sentences, which he intended to piece together, and out of those rich materials, to give the world a complete body of all arts and sciences which, however, might be still improved, and much expedited, if the public would raise a fund.[1]

Just as Gulliver’s machine recomposed sentences to produce an encyclopaedia of thought, the embroidered words of Rodari, placed in Sara Basta’s “combinatorial machine,” travelled the streets of the neighbourhood to create a polyphony of multiple stories and new paths of affection. With the same women from the workshop and guided by the same artist, the words, left to act on the streets of the Trullo, came together in the eighth lot courtyard, where our journey into the neighbourhood began. These words mark a moment of rebirth, and also represent a struggle, a constant battle for one’s rights, for one’s freedom. The words here are shouted, through songs in the folk tradition “And we’ll fight for work, education, play and for freedom”. Moto perpetuo combinatorio turns into song, a rebellious song of unfettered voices[2], that we hope will continue to act and resonate among the colourful streets of the Trullo.

Benedetta Carpi De Resmini

[1] J. Swift, Gulliver’s Travel, CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, pag.152

[2] Brancoro is a bunch of unchained voices. Their song is antifascist, anticlerical, antisexist and antimilitarist.